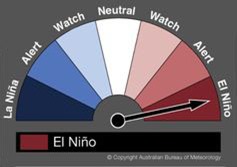

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) has now officially declared the arrival of El Niño 2015. And its expected to be a significant event.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) has now officially declared the arrival of El Niño 2015. And its expected to be a significant event.

The last El Nino five years ago had a major impact with monsoons in Southeast Asia, droughts in southern Australia, the Philippines and Ecuador, blizzards in the United States, heatwaves in Brazil and killer floods in Mexico.

In the Pacific, El Niño could increase the likelihood

of cyclones and severe storms by 30% and

increase cyclone intensity (maximum sustained wind

speed) and severity (potential impacts),

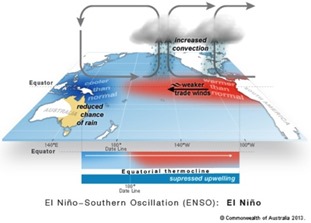

compared with ‘normal’ years. El Niño is a climate pattern which part of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon. This is an oscillation between a warm (El Niño) and a cold (La Nina) state, and evolves under the influence of the dynamic interaction between atmosphere and ocean, with an irregular frequency of 2–7 years.

In simple terms, El Niño occurs when some of the warmest ocean waters in the world – northeast of Papua New Guinea, where the ocean can exceed 30C – shift east towards South America. As the warmth shifts east, so do the clouds and rain. And the fish.

El Nino versus La Nina

El Nino is the warm phase of the ENSO cycle. It features warmer than normal Sea Surface Temperatures (SSTs) across the Central and Eastern equatorial Pacific along with weaker low-level atmospheric winds along the equator and enhanced convection across the entire equatorial Pacific. Effects are strongest during northern hemisphere winter because ocean temperatures worldwide are at their warmest. The increased ocean warmth and convection alters the jet stream.

In contrast, the La Nina cool phase of the ENSO cycle features cooler than normal SSTs across the central and eastern equatorial Pacific along with stronger low-level atmospheric winds along the equator and decreased convection across the entire equatorial Pacific. These result in a more suppressed southern jet stream. Droughts in Tuvalu are associated with La Nina events (like 2011).

SST: El Nino SST: La Nina

Image: http://www.nc-climate.ncsu.edu/climate/patterns/ENSO.html

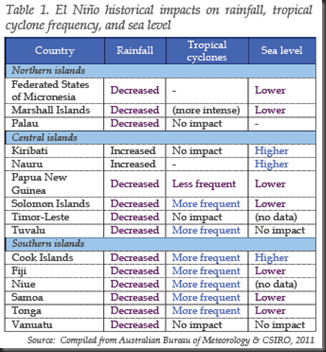

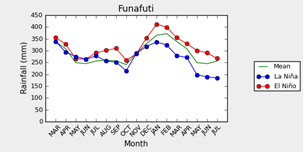

Left: ESCAP 2014 Effects of El Nino; Right: Funafuti rainfall composite during all years, El Niño / La Niña events. Analysis: A.Cottril, Data: Pacific Climate Change Science Project, Tuvalu Meteorological Service (http://informet.net/tuvmet/). These two figures contradict for rainfall with ESCAP saying our rainfall will decrease and PCCSP saying it will increase.

A boost to Fisheries

The oceanic fisheries of the tropical Pacific Ocean are of great importance to many

of the economies and people of the region. The four main species in these oceanic fisheries are skipjack, yellowfin, bigeye and

South Pacific albacore tuna. Across the wider Western and Central Pacific Ocean (WCPO) these yield catches of about 2.5 million tonnes a year and support fishing operations ranging from industrial

fleets to subsistence catches (Bell et al 2011).

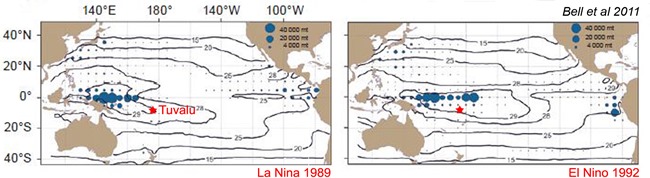

Changes in climate, such as variations in sea surface temperature, can affect the

distribution and migration patterns of marine fish, the survival of larvae and the recruitment of young fish. The most well-known of these is the large-scale, east-west displacements of skipjack tuna in the equatorial Pacific,

which are correlated with ENSO events. Driven by trade winds, the Southern and Northern Equatorial Currents interact to form a ’Warm Pool’ of water in the west, and an area of divergence and upwelling, called the Pacific Equatorial Divergence (PEQD) province in the central and Eastern Pacific. The PEQD is a surface cold tongue of upwelling waters rich in nutrients. The Warm Pool is favoured by skipjack tunas. As the ENSO changes between El Nino and La Nina, so the fish move with the water bodies, temporarily changing the face of fishing in the Pacific.

In El Niño years fish tend to be more abundant in Tuvalu waters, while in La Nina years, the opposite is true. We can expect better catches of skipjack in Tuvalu this year.

How does BOM decide on El Niño?

According to BOM: El Niño thresholds have been exceeded in the latest monthly and weekly tropical Pacific oceanic and atmospheric data. Sea surface temperatures are now at least 0.8 °C above normal; the western Pacific trade winds have been persistently weak; and the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) continues to be negative. Climate models monitored by the Bureau suggest the tropical Pacific Ocean will continue to warm in coming months, remaining above El Niño levels. Any three of the following criteria need to be satisfied for El Niño: 1. Sea surface temperature (SST): Temperatures in the NINO3 or NINO3.4 regions of the Pacific Ocean are 0.8 °C warmer than average. 2. Winds: Trade winds have been weaker than average in the western or central equatorial Pacific Ocean during any three of the last four months. 3. Southern Oscillation Index (SOI): The three-month average SOI is –7 or lower. 4. Models: A majority of surveyed climate models show warming to at least 0.8 °C above average in the NINO3 or NINO3.4 regions of the Pacific until the end of the year.

According to BOM: El Niño thresholds have been exceeded in the latest monthly and weekly tropical Pacific oceanic and atmospheric data. Sea surface temperatures are now at least 0.8 °C above normal; the western Pacific trade winds have been persistently weak; and the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) continues to be negative. Climate models monitored by the Bureau suggest the tropical Pacific Ocean will continue to warm in coming months, remaining above El Niño levels. Any three of the following criteria need to be satisfied for El Niño: 1. Sea surface temperature (SST): Temperatures in the NINO3 or NINO3.4 regions of the Pacific Ocean are 0.8 °C warmer than average. 2. Winds: Trade winds have been weaker than average in the western or central equatorial Pacific Ocean during any three of the last four months. 3. Southern Oscillation Index (SOI): The three-month average SOI is –7 or lower. 4. Models: A majority of surveyed climate models show warming to at least 0.8 °C above average in the NINO3 or NINO3.4 regions of the Pacific until the end of the year.

Some of those changes in the atmosphere (such as a weakening of the trade winds) actually help the ocean warm even more. This in turn drives more changes in the atmosphere. This leads to what BOM calls a ‘positive feedback’ loop, which ‘couples’ the ocean and the atmosphere. This means the El Niño is likely to be with us until the natural annual cycle of sea surface temperature ends the event early the following year.

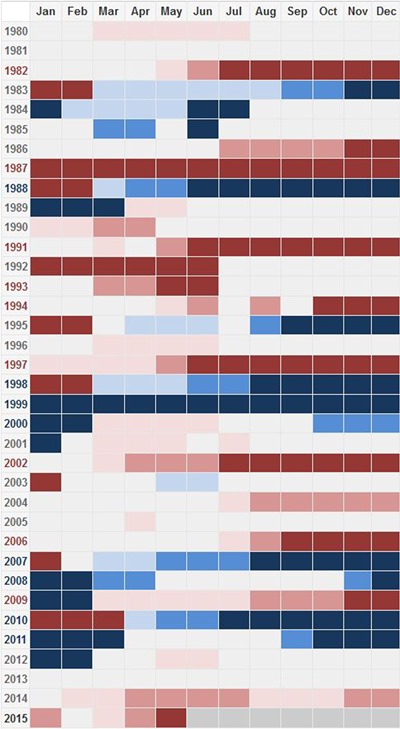

ENSO History

Here is the status of the ENSO tracker from the BOM website since 1980. The graphic shows the ENSO status by month, with the red year labels signalling El Niño-dominated years.

What does this mean for Tuvalu?

In Tuvalu we can expect the ocean to be warmer. We can also expect the rainfall to be higher than ‘normal’ this year, especially in the North of the country. In the South rainfall may actually go down. We may also see more cyclones than ‘normal’.

But the good news is that we will inherit the fish moving East from around PNG as they follow the shifting Warm Pool. Solomon Islands has already expressed interest in a vessel licensing pooling arrangement with Tuvalu for foreign fishing vessels which would act as an El Niño / La Nina insurance policy for both countries.

Sources

BOM ENSO Tracker: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/tracker/#tabs=Summary

BOM: We’re calling it, the 2015 El Niño is here: https://theconversation.com/bom-were-calling-it-the-2015-el-nino-is-here-41598

El Nino will be ‘substantial’, warn Australian scientists: http://news.yahoo.com/el-nino-weather-system-begins-tropical-pacific-australia-053103198.html

Global Patterns – El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO): http://www.nc-climate.ncsu.edu/climate/patterns/ENSO.html

Andrew Charles, Yuriy Kuleshov and David Jones 2012. Managing Climate Risk with Seasonal Forecasts, Risk Management – Current Issues and Challenges, Dr. Nerija Banaitiene (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-0747-7, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/51334. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/risk-management-current-issues-and-challenges/managing-climate-risk-with-seasonal-forecasts

ESCAP 2014 El Niño 2014/2015: Impact Outlook and Policy Implications for Pacific Islands

Bell, J. D., et al., 2011. Vulnerability of Tropical Pacific Fisheries and Aquaculture to Climate Change. Secretariat of the Pacific Community, Noumea, 929pp.